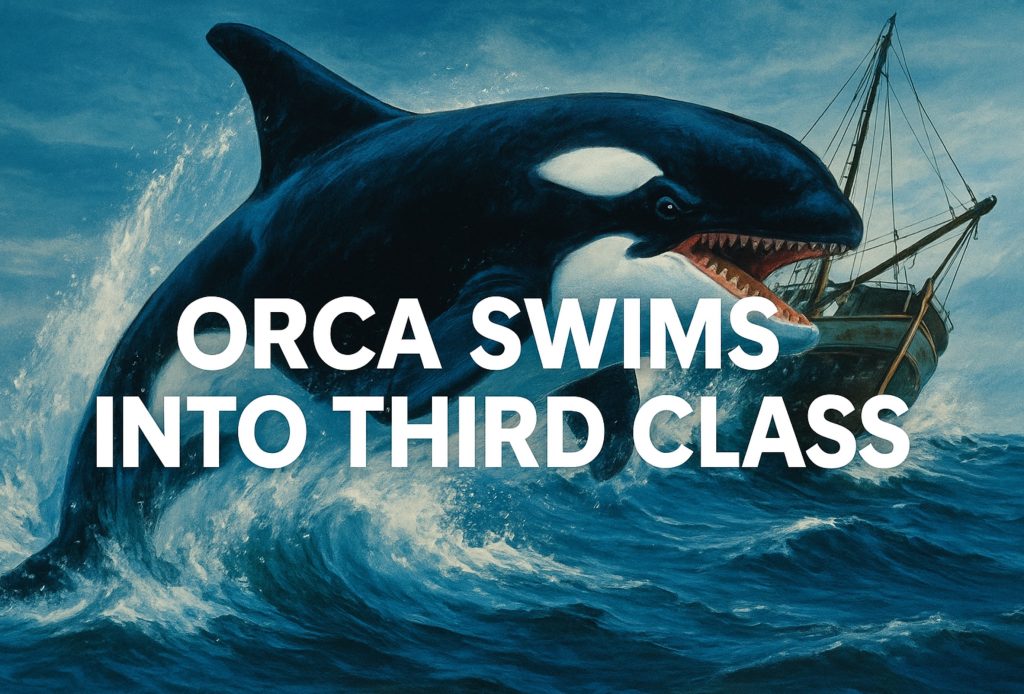

Orca Swims into Third Class of the Hall of Killers

Move over sharks, the whale has entered the water. The vengeful star of Orca from 1977 has officially swum his way into the Hall of Killers, finding a home in the third class tier. It is an honor reserved for cult favorites, underappreciated oddities, and the kind of killers that might not headline a billion dollar franchise but whose legacy refuses to sink.

Yes, this means Orca finally gets the recognition it deserves, part tragedy, part creature feature, part “what on earth were they thinking,” and all heart. The story of a killer whale seeking revenge after witnessing the brutal death of his mate is still one of the most operatic examples of aquatic vengeance in cinema. If Jaws was nature’s rage, Orca was nature’s grief.

Directed by Michael Anderson, known for Logan’s Run, and starring Richard Harris, Charlotte Rampling, and a surprisingly expressive whale puppet, the film dove into theaters during the great wave of animal attack films that followed Spielberg’s Jaws. Studios everywhere were desperate for another marine monster hit, and the black and white whale answered the call not with pure terror, but with a melancholy revenge story that felt like Moby Dick filtered through an Italian melodrama.

In the film, Captain Nolan, played by Harris, accidentally kills a pregnant orca, an act that unleashes one of the most poetic vendettas in horror history. The grieving whale systematically dismantles Nolan’s life, sinks his ship, destroys his crew, and drives him toward an icy death in the Arctic. Somewhere, Captain Ahab was nodding in approval.

It is this strange mix of pulp and pathos that earns our favourite killer whale its place in the third class. The Hall of Killers third tier is not about failure, it is about appreciation for the cult icons, the underdogs, and the horror curiosities that swim just outside the mainstream. These are the killers that live rent free in our collective imagination, not because they scared us the most, but because they were unforgettable in their own peculiar way.

Orca is a shining example. Its tone veers between heartbreaking and gloriously over the top, yet it somehow works. The performances are sincere, the visuals are striking, and Ennio Morricone’s sweeping score turns this fish tale into an underwater opera. The music is so haunting it could make a whale weep, which feels appropriate given that the film’s entire emotional engine runs on tragedy and saltwater tears.

Critics at the time were not kind, accusing the movie of trying to ride the success of Jaws. But while Jaws gave us the fear of the deep, Orca gave us empathy for it. The film dared to make the killer a victim too, and that twist of emotional depth has helped it endure. Today, the movie enjoys cult status among horror fans, animal attack enthusiasts, and anyone who appreciates a killer whale that plots revenge with the precision of a Shakespearean villain.

Its promotion to the third class of the Hall of Killers feels both fitting and overdue. It might not have spawned sequels or a massive franchise, but the Killer Whale has a loyal fanbase and a legacy that refuses to die. It stands as proof that even the strangest corners of horror history can resurface to claim their due.

So congratulations to our blubbery avenger. He may not have been the blockbuster Universal wanted, but it remains one of the most unforgettable revenge of nature stories ever filmed. A killer whale with trauma, a tragic backstory, and the acting chops to rival Richard Harris deserves applause and maybe a respectful splash.

Some killers come from nightmares, others from the sea. And this one just wanted justice for his family.